(Brief note: this article was written some time before the release, at long last, of Scrivener for iPad. You can read what I have to say about it here.)

In my mind, you're letting out a little silent groan: what, he's on about writing software again?

I swear, this is the last time.

A quick recap: last year, I wrote a post about different bits of software you could use to write books on a Mac, and it got the most hits of any single post I've written on my blog, ever. I wrote several follow-up posts here, here, and here. I was particularly interested in the ability to write on an iPad. Most of my writing takes place in a room where I sit, on my own, with a Macbook, but occasionally I like to venture out, perhaps to a cafe or the park; and, if the ability is there, it's nice to whip out the tablet while on the subway or waiting at the doctors and maybe read over what I wrote earlier that day and edit it a little.

You can't do that with Scrivener. There was talk of an iPad app last year, but they're back to not making any promises. If it comes out - if it ever comes out - I'll buy it. But I'm not holding my breath.

Why is it important? Because a lot of people want to be able to synch their writing across multiple platforms. A lot of people have iPads or similar, and want to be able to use them for writing, usually with a bluetooth keyboard.

Last year I bought Ulysses for both my iPad and Macbook (it's Mac-specific). It's a really terrific little piece of software that syncs very adequately and speedily between the two devices. In that respect, it's everything I'd been hoping to get from an iPad version of Scrivener.

But there are differences. Ulysses in its desktop incarnation is, relative to Scrivener, a much simpler program. Some people prefer Ulysses to Scrivener for that reason, since it lacks the bells and whistles of the latter. I never quite understood that myself, because over the years I've had many occasions (not necessarily out of choice) to use Microsoft Word for nothing more complicated than writing a letter or an invoice or perhaps following tracked edits from an editor, yet the fact it can do a whole bunch of highly complicated things beyond just typing text doesn't fill me with fear. I simply don't use them.

It's the same with Scrivener. The program has functions I've never used because I can't see a need for them. That's not the same for everyone - non-fiction writers, in particular, would probably get a lot of use out of those functions.

Since I got Ulysses, I've used it for a variety of tasks: writing outlines for new books, averaging roughly ten thousand words each; writing reports on unpublished manuscripts for a manuscript agency; several short stories, and ideas for more stories as well.

But the one thing I haven't yet tried to use it for is writing a full-length book. Nearly all of my books have been written in Scrivener. Would I be able to write one in Ulysses? I knew writers who have and still do. I figured I could at least try and see how Ulysses worked out in that respect.

But I was barely three thousand words into Field of Bones before I exported the text and notes, and imported it all into a new Scrivener document.

So why did I give up on writing a novel in Ulysses so quickly? A book is a huge and complex project that requires constant reference to character lists, invented history (in a science fiction novel), an outline so events being written about can be related to events already written or soon to be written, and also notes of moment-of-inspiration ideas for the next draft. I need to be able to see as much of that as possible, all at once, so I can literally see both the forest and the tree in front of me at one and the same time. I can do that easily in Scrivener; in Ulysses, it's a more difficult and considerably less intuitive process. Ulysses lends itself to a much simpler form of writing, one that has little to do with the workaday reality of plot construction and character arcs.

Writing a novel, for me at least, is not simple. It's huge and messy and tangled and difficult. I wrote my last book, Survival Game (due in August) in Scrivener, before I bought Ulysses. I hadn't yet tried a whole novel in Ulysses, and Field of Bones was to be my first attempt.

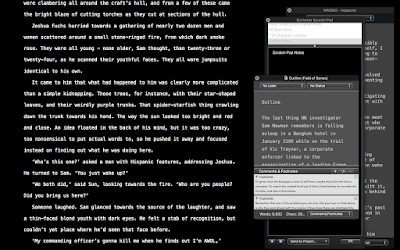

Now that I've imported it into Scrivener, this is what I see when I'm working on it:

On the left, in Scrivener's main window, is some of the text from the rough first draft of the first chapter. On the right is a series of stacked windows I can rearrange and move about and change the colours of and essentially do whatever the hell I like with: there's a scratch pad in which I can write multiple on-the-fly rough notes, a 'quick reference' window that allows me to open up multiple other documents to float over or next to the text, and an 'inspector' that again allows me to access a synopsis, multiple project-wide notes, chapter-specific notes, keywords, external online references, and on, and on, and on. I can move it all around and rearrange and close it and reopen it and resize it all just about any damn way I like.

For a writer, being able to do and see all of this at once is hugely empowering. It's like being a pilot and having the ability to glance at the cockpit dashboard and see exactly the information you need with minimal effort. In this respect, trying to use Ulysses to write a book reminded me of just how powerful Scrivener really is. It's the Godzilla of word processors, the all-time heavyweight champion; sometimes a bit fugly, but brutally powerful and easily adaptable to a multitude of personal preferences and habits.

Try as I might - and I have tried - I just can't do that with Ulysses, at least not with a novel. Ulysses is fine for shorter works, reports, short stories, ideas, outlines and all the rest of it: but as soon as I was ready to do something more ambitious, like a book, suddenly the only thing left to do was go back to Scrivener.

And that's despite its lack of an iPad app. Probably it helps that it's winter here in Taiwan right now, and it's chilly outside, so I'm more inclined to stay indoors and work at my desk. Maybe in a few months I'll yearn to work on the book outdoors. I could take the Macbook out, but it's heavy and the keys are buggered, necessitating a stand and an external keyboard. Or maybe I'll save those days for working on book reports, short stories and outlines with Ulysses.

So, then, let me offer my absolutely final, if personal verdict on Ulysses vs Scrivener, within the specific context of writing a novel. If you absolutely, positively, must have a writing program that syncs easily and smoothly with its desktop version, and you're okay with it being Mac-specific, Ulysses is a terrific little program.

But in all other respects, not to mention the fact it's available on multiple desktop OS's, I'm going to have to declare Scrivener the all-time champion for writing a novel. For the way I write, and for what it can do, it simply can't be beaten. Therefore if being able to write on the iPad isn't a major priority, buying Scrivener is the best thing you can do for your workflow as a working writer if what you're writing is a book. The end.

And I promise, no more posts on the subject. Ever. Err...probably.

*****UPDATE*****. Because putting an update in here is less embarrassing than actually writing another blog post on the subject when I promised no more blog posts on the subject.

Back when I started playing around with alternative word processors (as in, alternatives to Scrivener) like Ulysses, I also tried the iPad version of a program called Storyist and found it wanting. Like Ulysses, it has both a desktop and a tablet version, but although I tried a demo of the desktop Storyist I only actually shelled out for the iPad version. I used it a few times, but that was it.

The one big change between now and then is that Storyist will now allow you to edit Scrivener projects. That is huge. It's not a perfect solution by any means, but it's a damn sight better than any of the other attempts at linking Scrivener on the desktop to other word processors on the iPad. Usually, when you use other programs to open a Scrivener project, you're faced with a bunch of randomly named files with no clue as to which is the chapter you were last working on.

Storyist doesn't do that. I gave it a quick test run the other day on my iPad and it syncs very well indeed over iCloud - I usually store my working files on Dropbox, which I prefer to iCloud, but opening a Scrivener project stored in Dropbox in iPad Storyist, while feasible, isn't nearly as smooth. This apparently is partly down to the way Dropbox works.

But what really matters - and what you should take away from this - is that while there may not be a Scrivener iPad app yet, opening Scrivener projects on an iPad using Storyist seems so far like a very acceptable halfway solution. This, of course, puts Scrivener even higher above the competition like Ulysses.

In my mind, you're letting out a little silent groan: what, he's on about writing software again?

I swear, this is the last time.

A quick recap: last year, I wrote a post about different bits of software you could use to write books on a Mac, and it got the most hits of any single post I've written on my blog, ever. I wrote several follow-up posts here, here, and here. I was particularly interested in the ability to write on an iPad. Most of my writing takes place in a room where I sit, on my own, with a Macbook, but occasionally I like to venture out, perhaps to a cafe or the park; and, if the ability is there, it's nice to whip out the tablet while on the subway or waiting at the doctors and maybe read over what I wrote earlier that day and edit it a little.

You can't do that with Scrivener. There was talk of an iPad app last year, but they're back to not making any promises. If it comes out - if it ever comes out - I'll buy it. But I'm not holding my breath.

Why is it important? Because a lot of people want to be able to synch their writing across multiple platforms. A lot of people have iPads or similar, and want to be able to use them for writing, usually with a bluetooth keyboard.

Last year I bought Ulysses for both my iPad and Macbook (it's Mac-specific). It's a really terrific little piece of software that syncs very adequately and speedily between the two devices. In that respect, it's everything I'd been hoping to get from an iPad version of Scrivener.

But there are differences. Ulysses in its desktop incarnation is, relative to Scrivener, a much simpler program. Some people prefer Ulysses to Scrivener for that reason, since it lacks the bells and whistles of the latter. I never quite understood that myself, because over the years I've had many occasions (not necessarily out of choice) to use Microsoft Word for nothing more complicated than writing a letter or an invoice or perhaps following tracked edits from an editor, yet the fact it can do a whole bunch of highly complicated things beyond just typing text doesn't fill me with fear. I simply don't use them.

It's the same with Scrivener. The program has functions I've never used because I can't see a need for them. That's not the same for everyone - non-fiction writers, in particular, would probably get a lot of use out of those functions.

Since I got Ulysses, I've used it for a variety of tasks: writing outlines for new books, averaging roughly ten thousand words each; writing reports on unpublished manuscripts for a manuscript agency; several short stories, and ideas for more stories as well.

But the one thing I haven't yet tried to use it for is writing a full-length book. Nearly all of my books have been written in Scrivener. Would I be able to write one in Ulysses? I knew writers who have and still do. I figured I could at least try and see how Ulysses worked out in that respect.

But I was barely three thousand words into Field of Bones before I exported the text and notes, and imported it all into a new Scrivener document.

So why did I give up on writing a novel in Ulysses so quickly? A book is a huge and complex project that requires constant reference to character lists, invented history (in a science fiction novel), an outline so events being written about can be related to events already written or soon to be written, and also notes of moment-of-inspiration ideas for the next draft. I need to be able to see as much of that as possible, all at once, so I can literally see both the forest and the tree in front of me at one and the same time. I can do that easily in Scrivener; in Ulysses, it's a more difficult and considerably less intuitive process. Ulysses lends itself to a much simpler form of writing, one that has little to do with the workaday reality of plot construction and character arcs.

Writing a novel, for me at least, is not simple. It's huge and messy and tangled and difficult. I wrote my last book, Survival Game (due in August) in Scrivener, before I bought Ulysses. I hadn't yet tried a whole novel in Ulysses, and Field of Bones was to be my first attempt.

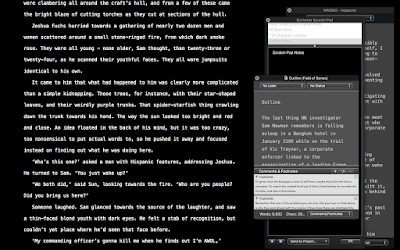

Now that I've imported it into Scrivener, this is what I see when I'm working on it:

On the left, in Scrivener's main window, is some of the text from the rough first draft of the first chapter. On the right is a series of stacked windows I can rearrange and move about and change the colours of and essentially do whatever the hell I like with: there's a scratch pad in which I can write multiple on-the-fly rough notes, a 'quick reference' window that allows me to open up multiple other documents to float over or next to the text, and an 'inspector' that again allows me to access a synopsis, multiple project-wide notes, chapter-specific notes, keywords, external online references, and on, and on, and on. I can move it all around and rearrange and close it and reopen it and resize it all just about any damn way I like.

For a writer, being able to do and see all of this at once is hugely empowering. It's like being a pilot and having the ability to glance at the cockpit dashboard and see exactly the information you need with minimal effort. In this respect, trying to use Ulysses to write a book reminded me of just how powerful Scrivener really is. It's the Godzilla of word processors, the all-time heavyweight champion; sometimes a bit fugly, but brutally powerful and easily adaptable to a multitude of personal preferences and habits.

Try as I might - and I have tried - I just can't do that with Ulysses, at least not with a novel. Ulysses is fine for shorter works, reports, short stories, ideas, outlines and all the rest of it: but as soon as I was ready to do something more ambitious, like a book, suddenly the only thing left to do was go back to Scrivener.

And that's despite its lack of an iPad app. Probably it helps that it's winter here in Taiwan right now, and it's chilly outside, so I'm more inclined to stay indoors and work at my desk. Maybe in a few months I'll yearn to work on the book outdoors. I could take the Macbook out, but it's heavy and the keys are buggered, necessitating a stand and an external keyboard. Or maybe I'll save those days for working on book reports, short stories and outlines with Ulysses.

So, then, let me offer my absolutely final, if personal verdict on Ulysses vs Scrivener, within the specific context of writing a novel. If you absolutely, positively, must have a writing program that syncs easily and smoothly with its desktop version, and you're okay with it being Mac-specific, Ulysses is a terrific little program.

But in all other respects, not to mention the fact it's available on multiple desktop OS's, I'm going to have to declare Scrivener the all-time champion for writing a novel. For the way I write, and for what it can do, it simply can't be beaten. Therefore if being able to write on the iPad isn't a major priority, buying Scrivener is the best thing you can do for your workflow as a working writer if what you're writing is a book. The end.

And I promise, no more posts on the subject. Ever. Err...probably.

*****UPDATE*****. Because putting an update in here is less embarrassing than actually writing another blog post on the subject when I promised no more blog posts on the subject.

Back when I started playing around with alternative word processors (as in, alternatives to Scrivener) like Ulysses, I also tried the iPad version of a program called Storyist and found it wanting. Like Ulysses, it has both a desktop and a tablet version, but although I tried a demo of the desktop Storyist I only actually shelled out for the iPad version. I used it a few times, but that was it.

The one big change between now and then is that Storyist will now allow you to edit Scrivener projects. That is huge. It's not a perfect solution by any means, but it's a damn sight better than any of the other attempts at linking Scrivener on the desktop to other word processors on the iPad. Usually, when you use other programs to open a Scrivener project, you're faced with a bunch of randomly named files with no clue as to which is the chapter you were last working on.

Storyist doesn't do that. I gave it a quick test run the other day on my iPad and it syncs very well indeed over iCloud - I usually store my working files on Dropbox, which I prefer to iCloud, but opening a Scrivener project stored in Dropbox in iPad Storyist, while feasible, isn't nearly as smooth. This apparently is partly down to the way Dropbox works.

But what really matters - and what you should take away from this - is that while there may not be a Scrivener iPad app yet, opening Scrivener projects on an iPad using Storyist seems so far like a very acceptable halfway solution. This, of course, puts Scrivener even higher above the competition like Ulysses.